Moray Sky at Night

January 2023

Moon Phases January 2023

Full Moon 6th,

Last quarter 15th,

New moon 21st,

First quarter 28th Jan ’22.

Image courtesy of https://moonphases.co.uk

The Planets

Mercury ~ Passes inferior conjunction on 7th January.

Venus ~ Close to the Sun in twilight although bright at Mag -3.9.

Mars ~ In Taurus, slowly fading from mag -1.2 to -0.3 over the month. It is occulted by the Moon on 3rd and 31st January.

Earth ~ Reaches perihelion (it’s closest point to the Sun in its yearly orbit) on 4th Jan at 16:17 UT, when its distance will be 0.983295578 AU/ (147,098,855 km).

Jupiter ~ In Pisces average Mag -2.0.

Saturn ~ In Capricornus at Mag 0.8, close to the sun in evening twilight..

Uranus ~ Initially retrograding until 23 Jan, mag +5.7.

Neptune ~ In Aquarius at Mag +7.9.

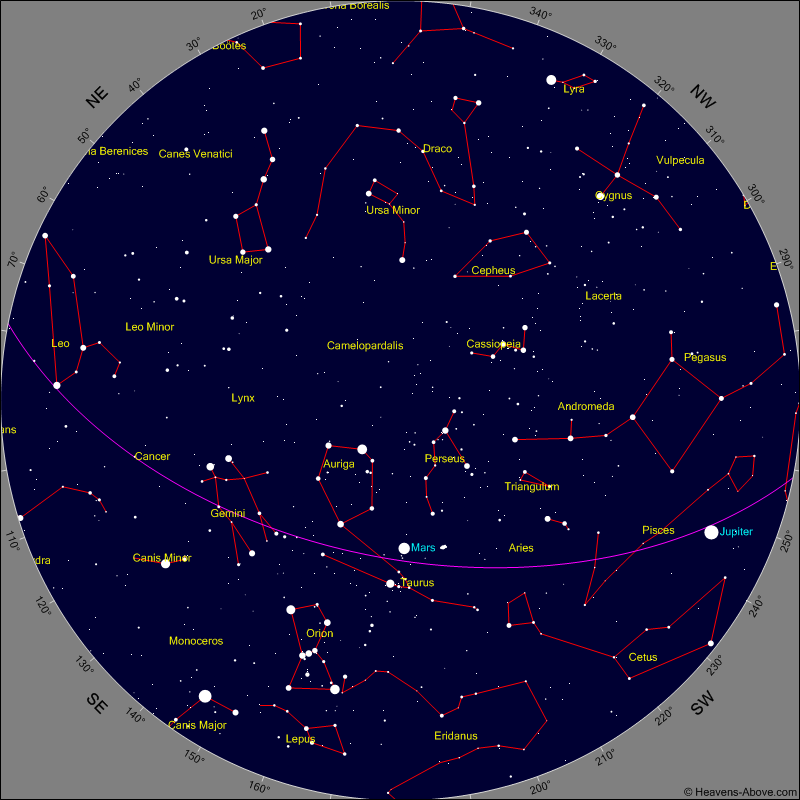

MORAY’S NIGHT SKY – 15th January 2023 @21:00 hrs GMT

Thanks to Chris Peat at Heavens-above.com for use of the star map

Meteor Showers

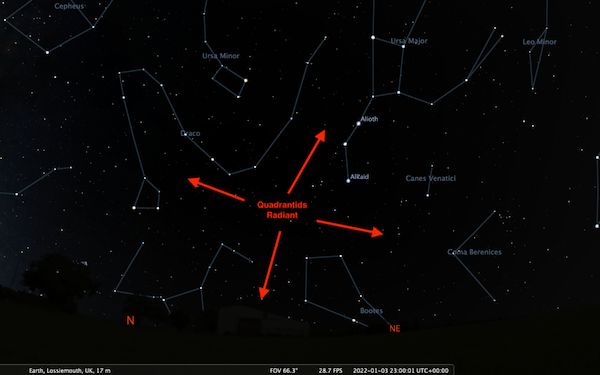

The Quadrantid meteor shower actually starts at towards the end of December, on the 28th Dec ’22 and continues until 12th Jan ‘23. It’s one of the strongest and most consistent meteor showers, reaching maximum on the night of 3-4th January, just before Full Moon, so moonlight will cause some interference. However, the meteors are bluish- or yellowish-white and may reach a maximum of 120 per hour. The shower is named after the former constellation Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), an early form of astronomical instrument. The Quadrantid radiant is now within the most northern part of Boötes, roughly halfway between q Bootis and t Herculis.

(Click image for larger view)

January Overview

The year begins with Mars remaining very bright and a decent size well into the New Year.

Brilliant Mars may prove a distraction from the stellar treats of winter but of course Orion, our signpost in the cold season, will be high and helpful throughout Christmas and the New Year. The great hunter will reach the meridian at mid-evening in mid-January. From Orion, it is easy to locate Aldebaran in Taurus to his north-west and Sirius in Canis Major to his south-east, with Castor and Pollux in Gemini and Capella in Auriga to his north, almost gracing the zenith at Christmas.

This splash of winter jewellery guides us into a treasure trove of deep-sky trinkets, at the expense of some of the sparser areas of the winter sky, such as Camelopardalis. For such a large animal, the celestial giraffe is inconspicuous, having no bright stars, but it sits in a prominent position in the north with its rump sitting on Perseus and head lying near the pole.

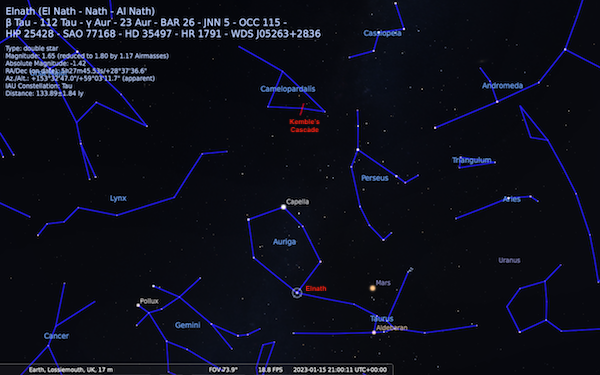

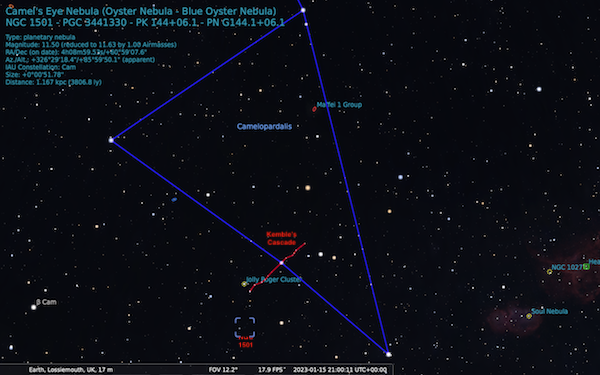

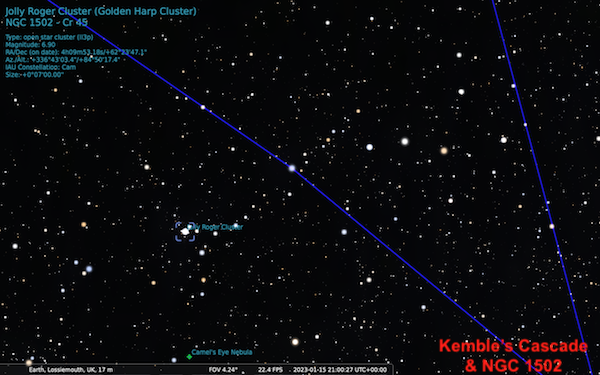

One of the best asterisms in the constellation is Kemble’s Cascade: a line of faintish stars covering a distance of around three degrees, so a treat using large binoculars. The stars are colourful too, adding to the beauty for imagers. Named by the legendary American amateur astronomer Walter Scott Houston, in honour of his friend Lucian Kemble who described it to him, it tips into the bright open cluster NGC 1502. Locating Kemble’s Cascade can be tricky (or fun, depending on your point of view), as there are no bright stars nearby to guide you and the high elevation can give neck pain. The easiest way (using the image above as a reference) is to start at Elnath (beta Tauri or gamma Aurigae) and sweep past Capella for a similar distance. You should then see the lines of 8th- to 10th-magnitude stars either side of a 5th-magnitude white B-type star. NGC 1502 itself (The Jolly Roger Cluster) is a compact seven arcminutes in diameter, so may be the most obvious component of the Cascade.

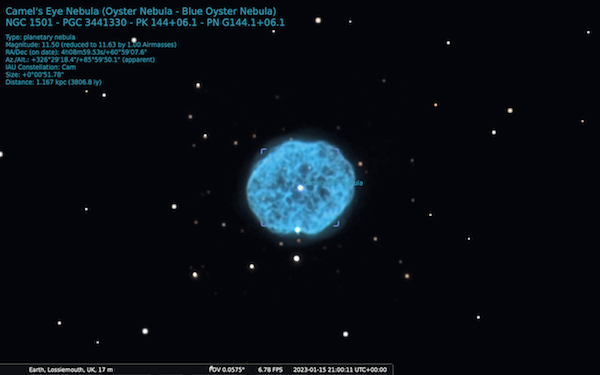

Just over a degree north from NGC 1502 lies NGC 1501, a very enjoyable planetary nebula (image above and below). It is nicknamed the Oyster Nebula – perhaps for the 14th-magnitude central ‘pearl’ – and despite an off-putting magnitude of 13, it is quite an easy bluish disc and a respectable 50 arcseconds across; it is not dissimilar to Jupiter in apparent size.

______________________________________________________

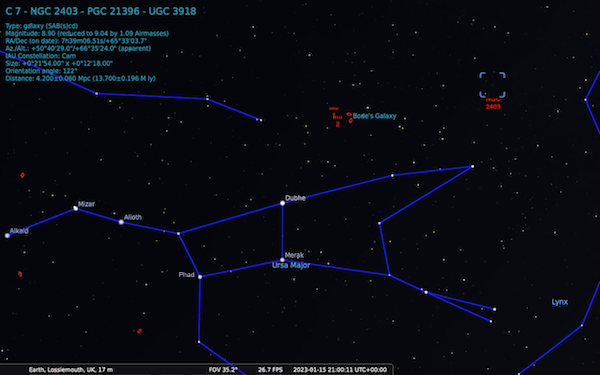

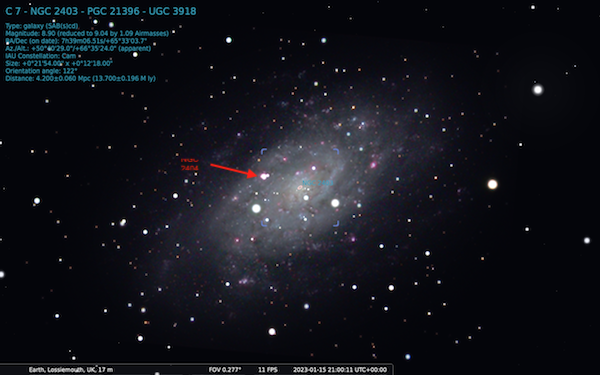

By the turn of the year, it is obvious that the Great Bear is on the move. Ursa Major turns into the north-eastern sky and Camelopardalis swings with it. Two other targets are easier to locate by using the ursine signpost, and both are in northern circumpolar positions. Firstly, the fine galaxy NGC 2403, thought to be part of the Messier 81 group and around nine million light-years from us. Its proximity makes it appear large, at 22×12 arcminutes. The huge H ii region NGC 2404 (within NGC 2403) is approaching 1,000 light-years in diameter, and the similarity of the galaxy and its H ii region to Local Group galaxy Messier 33 is striking. It is located between the heads of the Great Bear and Lynx, and some have glimpsed it with large binoculars. From Phad (gamma Ursae Majoris) through Dubhe (alpha Ursae Majoris) and past Messiers 81 and 82, deviate the same distance slightly to the south to locate the galaxy in a rather amorphic zone.

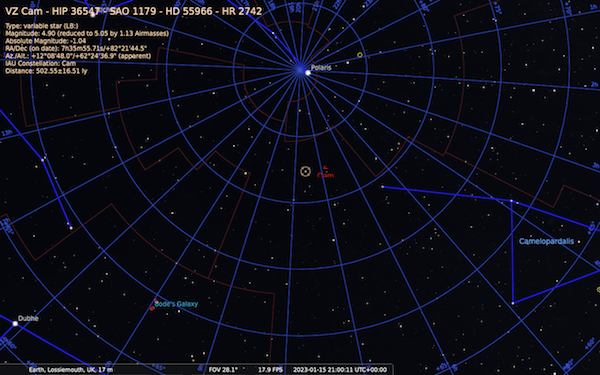

Then there is the cataclysmic variable star Z Camelopardalis: a dwarf nova that has a range between 9th and 14th magnitude. Z Cam is a popular variable and the prototype star of a subclass of dwarf-nova-type cataclysmic variables. These Z Cam stars are characterised by their random standstills in amplitude, differentiating them from the rather similar SS Cygni dwarf novae. The plateaux occur between the maximum and minimum range – in Z Cam’s case, around magnitude 11.7. The maximum is around 9.6, the minimum 13. The standstills occur as the star fades from maximum and may last days or even over a year, so as a circumpolar object it is always worth monitoring.

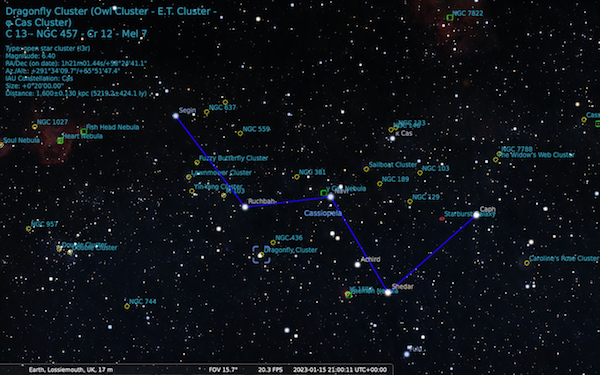

If the giraffe proves frustratingly elusive due to the dearth of bright guides, revert back to Cassiopeia for some browsing opportunities within the Milky Way. Remaining high in the north-west, the Milky Way runs through her and she is studded with bright open clusters that appeal to all, with Messiers 52 and 103 being striking examples, as are the Dragonfly Cluster (or Owl or E.T. Cluster) (NGC 457) and Caroline’s Rose Cluster (NGC 7789) that rival any in the heavens. The latter is named after Caroline Herschel, sister to William, and this large, jewelled brooch is rightly a favourite. Less well-known clusters are also worth exploring. NGC 663 lies between delta and epsilon Cassiopeiae and is very lovely, its close proximity to NGC 654 (The Lawnmower Cluster) adding to the spectacle. Exploring this rich region is most rewarding. (I’ve added an image to show some of the targets worth looking up).

For many observers, Orion and his winter retinue will dominate. Taurus, Canis Major, Auriga, Gemini and Lepus the hare getting under his feet are all stuffed with Christmas treats, familiar and less so. Monoceros is rising in the east too, best seen mid-evening in late January. The long winter nights are just so rich!

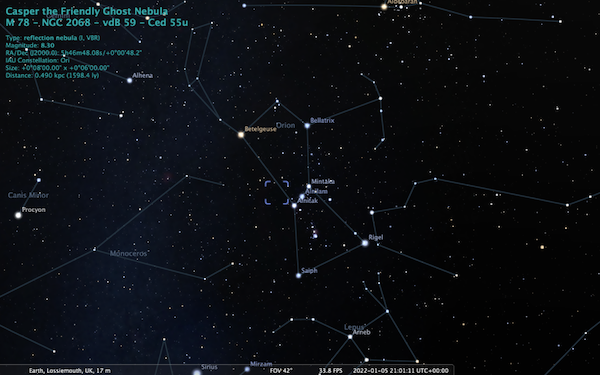

January’s Object Challenge

Messier 78 (M78) is a reflection nebula located in the constellation Orion, the Hunter. M78 is the brightest diffuse reflection nebula in the sky. It has an apparent magnitude of 8.3 and lies at an approximate distance of 1,600 light years from Earth. The nebula is pretty easy to find as it is located only about 2 degrees north and 1.5 degrees east of Alnitak, the easternmost star of Orion’s Belt. The nebula can easily be seen in large binoculars and small telescopes, which show a hazy, comet-like patch of light with two 10th magnitude stars that illuminate it. M78 is also visible in 10×50 binoculars as a dim patch, but it requires clear, dark skies to be seen.

This new image of the reflection nebula Messier 78 was captured using the Wide Field Imager camera on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory, Chile. This colour picture was created from many monochrome exposures taken through blue, yellow/green and red filters, supplemented by exposures through a filter that isolates light from glowing hydrogen gas. The total exposure times were 9, 9, 17.5 and 15.5 minutes per filter, respectively. Credit: ESO/Igor Chekalin

*Click image to enlarge Further information: https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1105a/

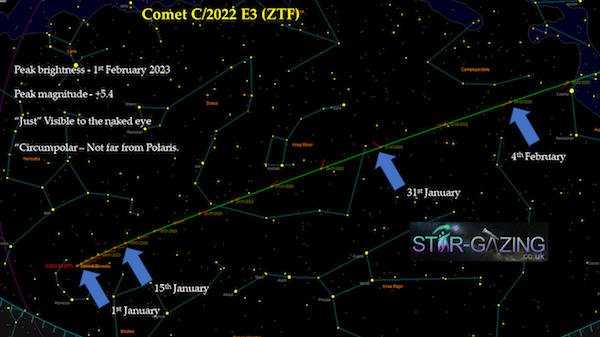

Comets

As mentioned in previous Newsletters and meetings , comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is well worth looking for and keeping an eye on. C/2022 E3 (ZTF) is a long period comet that was discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility on 2 March 2022. Upon discovery the comet had an apparent magnitude of 17.3 and was about 4.3 AU (640 million km) from the Sun. The object was initially identified as an asteroid, but subsequent observations revealed it had a very condensed coma, indicating it is a comet.

Image courtesy of www.stargazing.co.uk

It’s pretty barren time for comets, although C/2022 E3 (ZTF) will be well placed in the predawn sky after Christmas, moving slowly through Corona Borealis. It is gradually drawing closer and getting brighter, aiming for perihelion on 13 Jan ‘23 when at a distance of 1.11au from the Sun. After perihelion, it moves more swiftly through Boötes into Draco and becomes circumpolar, when it could be a binocular object all night.

It lies in Camelopardalis when closest to Earth on 02 Feb ‘23, at only 0.29au or 27 million miles (44 million kilometres), then moves close to Capella on 5 Feb ‘23. Our fingers are crossed for great sightings, but as always firm predictions of comets can always fall apart!

ISS

The ISS is a morning object until the 3rd January ‘23, after which it won’t be visible for us here. Then from the 19th Jan it becomes visible in the evening sky until the 3rd of February ‘23.

For more info go to https://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544 and if you make a free account there and enter your location it gives you a precise timing and starmaps.

Have a Happy New Year and best wishes to you all for 2023.

Clear skies!